RAYMOND FUNG: LANDSCAPES BETWEEN ART AND ARCHITECTURE

| December 1, 2011 | Post In LEAP 11

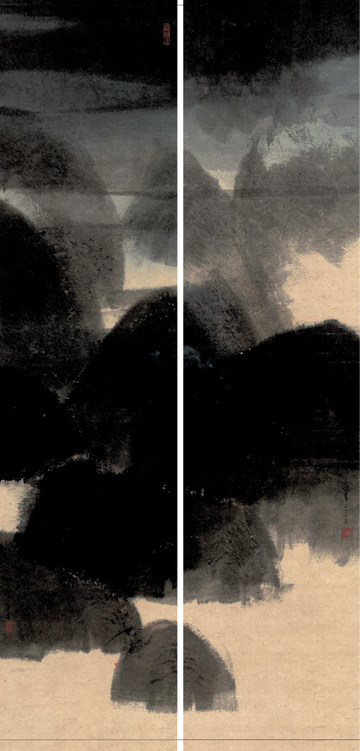

Once he discovered the professional and artistic work of one Raymond Fung, LEAP Contributing Editor Hans Ulrich Obrist took immediate interest. In Fung, Obrist saw a practitioner who had made real on the longtime crossover between art and architecture in a practice divided somewhat uncharacteristically into a “day job” as a municipal architect and a separate career as an ink painter. As Fung’s major solo exhibition “The Artistic World of Raymond Fung” concludes the Beijing stop on its world tour, we offer some excerpts from an interview with the former disciple of I.M. Pei in which Obrist aims to explore the similarities between Fung’s work in public and on paper.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: At the moment we have many artists who are also architects, such as Olafur Eliasson and Ai Weiwei. For a long time you have been both an artist and an architect. Could you talk a little bit about the bridge between art and architecture? What came first?

Raymond Fung: Well, in the first place, I am an artist, but not a professional one. As a kid I was so fond of art, of scribbling on paper, of trying to represent the things in my mind onto paper. Once I came into practice as architect, I tried to see how the two can mesh together. In any of my projects you can see a lot of little forms of art being incorporated. After I became an architect, I could make use of art; now I departed architecture and returned to art, but you can still see my Chinese painting contains a lot of space, the interplay of space, in a two dimensional piece of work.

HUO: Could you talk a little bit more about your work as a painter? Who are your influences in painting?

RF: Oh, first of all, the first one, very early on, was Zhang Daqian, in the early 1970s. Actually, I have one piece of work from my early period that somehow takes reference from his work. Later on I tried to create my own character, developing more over the years.

HUO: But then you were inspired by the traditional, as there is such a long distinguished history of Chinese painting. Wang Hui, from the seventeenth century, was a great pioneer. Who are the pioneers who inspire you from previous centuries?

RF: Oh, the pioneers. Before Zhang Daqian there were several guys. One was Shi Tao. Coming back to more recent times… maybe I should be more pragmatic. Let me see. More of a direct influence on me would be Lui Shou-kwan is the man, the influence in Hong Kong modern art. He is from the early 1960s. He’s no longer alive. But being more direct, I would consider me as the first person who influenced me.

HUO: Your paintings are always connected to landscape, or very often, correct?

RF: Yes, of course there are some, but most of them are just painted in Hong Kong.

HUO: Now when you paint, do you paint them very fast, or very slow? How do you work?

RF: Fast and slow. When I’m doing the big brush strokes, that has to be fast because they all come instantly. But once you come to the very meticulous details, that will take more time, so it comes with very bold form, then to the smaller forms, the smaller details.

HUO: And do you do sketches before doing big ones?

RF: No, no, no.

HUO: And is it a state of meditative concentration, what’s the state you put yourself into to do drawings?

RF: I think this state is just between the soul and the working position. I’m very strong in that, I don’t know how to explain that to people. It just happens.

HUO: Art happens.

RF: It all happens. When I have a big brush and I’m doing it onto the paper and I can start to create a kind of a contrast, being black or being white, being empty or being full.

HUO: Obviously, there is a long, long tradition of landscape painting in China. Do you think there has been progress?

RF: This is a very sensitive question, some say yes, some say no. So it depends. If you are looking from the Western perspective, there is no progress because they look so similar. But for me, I see there is progress.

HUO: So, within your own logic there is a progress.

RF: Yes there is a progress. Of course it goes very slow. Which I think is very natural to Chinese culture. Everything goes so slow. I think it always goes back to the mindset of the people. We are conservative, therefore we do everything one at a time, and therefore progress is very slow.

HUO: And you use a lot of horizontal formats. Why the extreme horizontality?

RF: I always want to limit myself to a certain format, and to work within that format. And maybe this is the kind of the pressure in life or maybe this is a very architectural attitude. I tried to squeeze myself into a very extreme format and to work within it, to work within and beyond it. If you look at my work, you have to see it from inside the outside. You can actually see that I’m trying to break through, that the whole composition itself is trying to work beyond this boundary.

HUO: Do you have any unrealized projects? Promenades? Dreams? Utopias?

RF: My favorite unrealized project… the museum of contemporary art.

HUO: Your museum of contemporary art never got built?

RF: I was given the job and it never got built. In Hong Kong we don’t have good quality museums built so far, and I was given the job, so I tried very, very hard to realize it, but unfortunately, it was shut down by some people over ten years ago. And now I’m waiting for another person to realize it in West Kowloon. But I’m not the architect any more; I’m just a member of the committee in West Kowloon.

Translated from English / Translation: Verona Leung

(Interview conducted in May 2009)