TWO ROADS DIVERGED: THE BEIJING INTERNATIONAL

| June 8, 2015 | Post In LEAP 32

PHOTO: Elaine W. Ho

The harsh realities of an industrializing country with one-fifth of the world’s population create a fertile climate for a unique and diverse cultural discourse. Beijing is a backdrop for real cultural exchange: western theory is debunked over dumpling dinners as Chinese philosophy is integrated, collaborations are conceived as artists walk from one café to another in search of faster internet access, and collectivity is solidified at late night experimental music performances in 600-year-old temples. The hutong alleys are a downtown of sorts, providing a proximity or density that allows for the free exchange of information, as well as a diversity that inspires spontaneity and collaboration. Within these ancient hutongs resides a network of expats—an array of artists, designers, architects, musicians, filmmakers, and writers who use central Beijing as a space to challenge conventional definitions of contemporary art as prescribed by institutions and propagated by market systems.

Taking advantage of Beijing’s locality, these individuals are “cultural operators … constantly questioning themselves, their methods, their practice, and their objectives,” according to Italian artist Alessandro Rolandi, as low (though rising) housing and production costs allow for unique alternative spaces and individual artistic practices that would elsewhere be constrained by the need for bread-and-butter jobs. Many alternative spaces and artistic practices within the second ring road are marked by a desire to engage and converse with local populations, giving them a DIY and process-driven aesthetic. While the many westerners who comprise the majority of this scene believe that Beijing’s center is representative of the city—its traditions, culture, and people—the inner second ring road is a rather antiquated and romanticized notion of the capital, leading to debates over the concept of authenticity in this artistic discourse. Removed from the pressures and potential for uniformity and stagnancy of theoretical discourse beholden to market and institutional frameworks, hybridity and experimentation reign in central Beijing. American artist Michelle Proksell notes, “Coming to China to produce is like entering a new frontier.… Personalities that choose to produce in this environment are already seeking and exploring alternative methodologies, which means they aren’t following any particular mainstream idea.”

Courtesy the artist

In 2011, Alessandro Rolandi developed the project Social Sensibility Research & Development (SSR+D) in collaboration with the French-owned company Bernard Controls. Operating a factory on the south fifth ring road, Bernard Controls agreed to re-appropriate their corporate social responsibility (CSR) budget to support an innovative project that has come to resemble an artist residency program. Over the past four years, Rolandi has invited 31 artists, himself included, into the factory for short residencies, where their sole mission is to create work specific to the factory population and space. Artists are given a small stipend and are allowed to utilize any material found on the factory floor. By reorienting the CSR budget to develop programming of benefit to the internal corporate work force, Rolandi locates a unique hybrid solution in which art is introduced as a tool to bolster the social adhesion of the employee population; the residency activates a dialogue that transforms the artist’s social role from one of passive observation and distant commentary to one of active engagement—art as a communicative tool. A funding structure is also sustained, serving as a potential future model for not-for-profit organizations and programming that support autonomous artistic practices. The project raises questions of culture being co-opted by capitalism, in that workers’ attitudes are enhanced and productivity and efficiency are increased, further integrating production into an optimized system. Nevertheless, distance from traditional practices of not-for-profit management allows for a break with established modes of operation, offering an alternative suitable for a more contemporary context. As seen in many of SSR+D’s projects, a large percentage of the work produced in the hutong scene emphasizes a return to praxis, where artists experiment with processes and a DIY aesthetic. While Beijing’s institutionalized discourse may not recognize SSR+D’s relevance, the project’s contributions to notions of hybrid practice are evident.

PHOTO: Wang Yang

The city’s vibrant energy propels this international crowd into endless collaborations and projects. Spaces like Zajia, a bar and performance venue that often hosts lectures and movie screenings; The Other Place, a café with space for talks and small DJ sets; Wujin, a breakfast bar and independent publication retailer; XP, a music venue for experimental music; and Dada , a late night dance club, all serve as nodes facilitating dialogue. Music venues like XP, Dada , and Yugong Yishan are testament to the eternal link between the music and DIY scenes in Beijing. Beginning with Beijing’s punk scene in the 1990s, westerners studying abroad have identified with this aesthetic, which, while rooted in the west, inevitably morphs to suit the styles of young Beijing musicians. As such, it is through punk, metal, rock, and now experimental music that foreigners embed themselves in and engage with Beijing’s cultural scene. It is this scene that, over the past 20 years, has evolved into the DIY art scene that locates itself inside the second ring—while it is detached from the institutionalized art world, it has its own center of gravity that inevitably influences other cultural scenes.

The Chinese audiences that heavily populate underground music shows ref lect how local youth populations follow the art scene via experimental music. Leading experimental musicians even traverse the institutional art world: Yan Jun floats between DIY and institutional, experimental and academic, and music, art, and publishing. Running the label Subjam, Yan has organized workshops teaching people how to make their own instruments at Vitamin Creative Space’s Beijing outpost, The Pavilion; held a monthly concert series at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art; and played household objects during performances at hutong galleries like Jiali. Known initially as an indie rock critic, he produced the publication Sub Jam (1998), which looks at the first wave of rock music in China.

There are also artists like Meng Qi, whose practice hovers between music, design, and engineering. Though his work is highly respected by musicians and technicians around the world, he has not yet entered Beijing’s institutional art world. Producing work that takes the form of instruments or experimental sound, it is likely that “the questions [he] asks in [his] work aren’t pertinent to those being asked by other artists. [As such, his] practice becomes insular and isolated,” despite adding to a dialogue relevant to his own community, according to Portland-based artist Joe Sneed, who engaged in social practice in Beijing. Perhaps this is the case with Meng Qi’s work, though his instruments can and should be situated within an academic discourse around the ongoing revolution of sound production away from digital synthesis and back towards instrumentation. But perhaps his personal desire to engage in music and not art world dialogues inhibits his acceptance by art world systems.

The snaking urban grid of Beijing’s central hutongs is a metaphor for the alternative spaces that populate it: small and community-oriented, they implement ideals stemming from western notions of the alternative space. Their projects are confluences of ideas and disciplines, and are often independently financed, perhaps as a challenge to the market. Working at a local level allows for affordable production: installation construction, rent for a project space, or printing for a periodical is often a fraction of what it would cost in the west.

PHOTO: Gao Ling

Nearly ten kilometers from the art districts of 798 and Caochangdi, where the majority of the institutionalized art world resides, a plethora of alternative spaces, galleries and studios have erupted in this central area. Arrow Factory and HomeShop, both founded in 2008 in opposition to the booming market, respectively serve and once served as community-centric venues for research, production, and dialogue. Arrow Factory refurbished an existing storefront for site-specific installations visible day and night, presenting provisional works by local and international artists. With no organized openings, their exhibitions are contingent on forming meaningful responses to the diverse economic, political, and social conditions of locality and lived experience. Still operating today, Arrow Factory relies on institutional support, donations, and savings from founders Rania Ho (USA), Wang Wei (PRC), Wei Weng (PRC/USA), and Pauline Yao (USA) (the latter two are no longer actively involved with the program). Though it does not directly challenge the commercial market by developing a new mode of sustainability, the space uses contemporary art to inject historical and political commentary into a traditional part of Beijing far from the commercial art scene.

Founded just months after Arrow Factory, HomeShop was a space for artists, designers, and thinkers to convene at the intersection of small-scale, community-based interventions. Though founded by Elaine Wing-Ah Ho (HK/USA) without intending to become a collective, it organically transformed into one. Including theorists and artists Michael Eddy (Canada), Fotini Lazaridou-Hatzigoga (Greece), and Ouyang Xiao (PRC/USA), among others, the collective challenged the relationship between public and private. Their literary journal, wear, was among the first published by the expat population, and intended to be “A meta-exchange by way of varying lenses of the cultural world (art and art history, architecture and urbanism, discourse theory and philosophy) that, after ping-pong, may have the possibility to turn outside of itself,” as Ho writes in the introduction of wear #2. The well-designed, bilingual publication set a precedent for projects like Concrete Flux, a thematically driven journal discussing urbanism in China, and Bajia, a hybrid journal activating certain functions of exhibition catalogues through cross-disciplinary discourse (Bajia is published by Bactagon and founded and edited by the author of this essay). As transience inhibits permanent social cohesion for expats anywhere, HomeShop was dismembered in 2013 as members relocated, and a rent spike meant the permanent closure of the space.

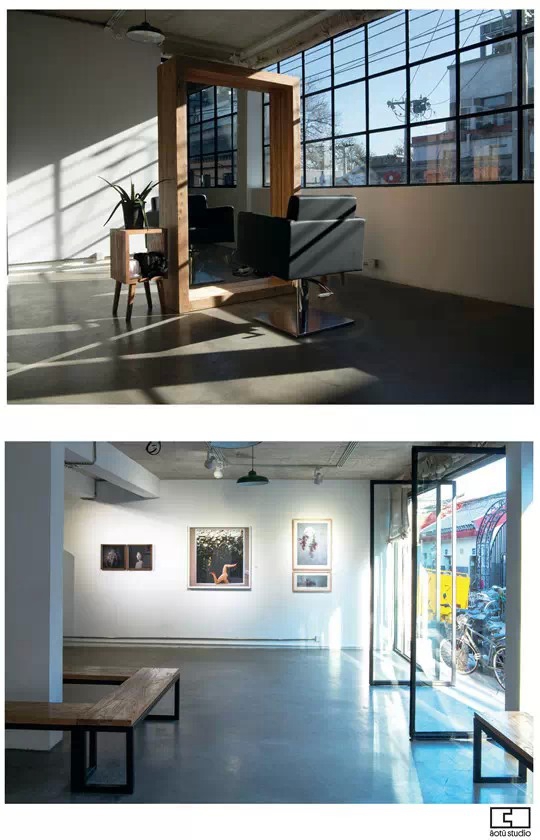

Two spaces descend directly from HomeShop: Aotu, a new hair salon and multipurpose art and design exhibition space run by Ray Wu (PRC) and Pilar Escuder (Spain), and Flicking Forehead Space, founded by Cici Wang (PRC), an exhibition and gathering space exploring non-market alternatives with a barter system. Asking participants to leave behind an object or work, Flicking Forehead has accrued a rather eclectic archive narrating its history.

The Institute for Provocation (IFP), first founded as Theatre in Motion in 2005 by Els Silvrants-Barclay (Belgium), serves as a residency, workspace, and think tank. The institute attempts to create knowledge “outside of the given framework for how to output knowledge in a traditional sense,” according to director Max Gerthel (Sweden). IFP aims to determine “what alternative forms of artistic, architectural research can contribute to society as a whole, and what kind of organizational forms can be established to accommodate these processes.” It also operates the new exhibition space Black Sesame.

A few blocks away sits I:project Space, a new residency and research-driven “platform for non-commercial art projects” founded by Anna-Viktoria Eschbach (Germany/Hungary) and Antonie Angerer (Germany). A block away is the gallery Intelligentsia. Run by Cruz Garcia (Puerto Rico) and Nathalie Frankowski (France), Intelligentsia is a two-year experiment in deciphering the relationships between ideology and contemporary art production. A two-minute bike ride away sits Jiali Gallery, literally translated as “gallery at home.” Located in the hutong home of Daphne Mallet (France), the program, while commercial, is a quaint alternative to 798, presenting emerging Chinese artists like Ren Bo and Ma Yongfeng.

The tight-knit interconnectivity of these centralized hutongs also poses drawbacks, namely the insularity of participants and audiences. Arrow Factory co-founder Rania Ho notes that “the relationship of the expat art scene to the local art scene might be described as a moon that orbits Saturn; one smaller spinning mass revolving around a larger spinning mass, both sharing gravitational forces.” It seems the reasons for this are manifold, though language and distance are significant. While programming is, for the most part, bilingual, English dominates inner second ring road conversations while Chinese is the language of choice for the institutionalized art world. Sadly, individuals who are both fully bilingual at an academic level and interested in participating and connecting both worlds are few and far between. Language aside, the inconvenience of distance in heavy traffic often means laziness and, more often than not, a critical eye, especially by those within the institutional realm.

As “precarious outsiders,” Alessandro Rolandi believes foreigners have the privilege of living as free agents detached from local norms and values that regulate social action—the privilege that lies at the root of the very criticism that the expat-centric DIY art world receives. Heavily influenced by altruistic western ideology, the vast majority of the hutong alternative spaces, projects, and practices strive to engage a local population with a cultural dialogue that is “pure” in its detachment from market systems. With the majority of Beijing’s middle-class population living between the third and fifth ring roads, however, and affordable housing (including for many Chinese artists participating in the institutional art world) primarily beyond the fifth ring road, the locals within the second ring are mostly elders who have lived there since the revolution or wealthy individuals in renovated courtyard homes, neither of which groups are broadly indicative of the city’s “local” population. As such, are the programs put forth by these alternative DIY spaces and artists honest or accurate in their local dialogues? And is the need for local authenticity relevant if these artists are collectively challenging conventional processes, if their experimental work is able to develop an authentic dialogue authentic within their own community? Or must it be situated within the institutional framework defined by the art world to be of significance? While there are “barriers, including language, political attitudes, common goals, and also a mutual lack of trust” that inhibit communication between these worlds, “there is great potential for a great dialogue, but also a great chance that this dialogue would just be about mutual pragmatic return instead of authentic transcultural exchange,” according to Rolandi.

Perhaps the palpable gap existing between these two distinct art worlds allows for the one within the second ring road to flourish in its own experimental, DIY, and cross-disciplinary way. Its expressive freedom certainly allows “local and foreign residents who are inclined to seek out the cultural fringe [to] find like-minded people that share their interest and enthusiasm,” according to Rania Ho, but “these small pockets of activity are relatively tiny blips in this sprawling metropolis, and most people don’t take much notice. This allows this peripheral activity to remain active and develop relatively undisturbed.” Whether or not this work has or will ever have credence in Beijing’s institutional art world remains to be seen—and might not matter at all. So long as institutional and market forces maintain their course, these alternative spaces and projects will remain alternative—engaging a community that is very much their own.

TEXT: Zandie Brockett

TRANSLATION: Xia Sheng