WOMEN IN COLOR

| August 6, 2015 | Post In 2015年6月号

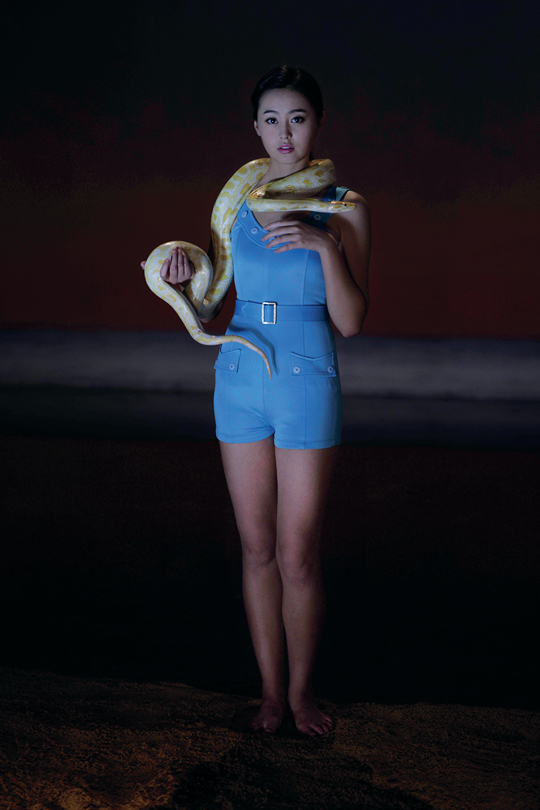

Courtesy ShanghART Gallery and the artist

Gauzy and alluring maidens sparkle across the screen in Yang Fudong’s new film; The Colored Sky: New Women II begs the question of what happened to the old women. It’s already part of a series, like Lacan’s understanding of male sexuality structured as an infinite series of individual encounters that never feels repetitive but appears tacky and pathological from the outside. Yang seems comfortable with what he likes; the male gaze is embraced wholeheartedly, with or without critique. As image, his work is somewhere between Amalia Ulman’s Instagram account and soft porn. Of course, Amalia is taking photographs of herself, while Yang shoots new women: it really never seems to get old for him.

Nymphs bound through a beach scene in front of shimmering panes of glass. It’s compelling, but not for the right reasons; it might be just a little bit NSFW. But these images produce an interesting effect: they are very precise, in that Yang seems to achieve exactly the sort of image he wants to, but, although they allude to various times and places obliquely, they don’t clearly belong anywhere in particular. Where would one go to find these new women? The beach where the videos are shot isn’t real. It is a creation of spectacle without any referent in reality, superimposed on the bodies (a gentleman might say faces) of young Chinese women. To say that these images seem immediately cliched is to recognize their success; actually, this type of images doesn’t appear elsewhere. Yang creates a cliche all his own; it’s painfully obvious, but creating a hitherto nonexistent discourse that, upon emerging, seems so logical as to be obvious is a goal that many artists aspire to. The objection that he treats women as readymades might become personal, but doesn’t seem relevant as criticism.

Courtesy ShanghART Gallery and the artist

New Women I, which debuted in Shanghai in 2014, immediately brings to light the uncomfortable fantasies of the viewer—he (or, less commonly, she) has seen or thought of this before, even if it’s something new. Black-and-white images recall Godard’s film Contempt, an arrogant auto-critique that stands out from the director’s other work due to the strong performance of sex bomb Brigitte Bardot. Objectified and fantasized about by all of the other characters and, by extension, Godard himself, Bardot perfectly symbolizes a certain form of the dolce vita, as specif ic to that place and time as it is universal—and embarrassing sensitive male viewers. Yang’s work, too, is nostalgic, but not really for any place. At what time did women like this lounge about in ateliers in this fashion? Not in 1930s Shanghai, although the work clearly alludes to the aesthetic of that time. The women of New Women II can’t be found on any beach, not even in Sanya. Nostalgia is the syrupy emotional equivalent of the humidity of southern China; it structures culture in a way rarely encountered up north. Filled with cultural references and allusions, Yang Fudong’s new women are nonetheless new; they have never existed anywhere except the artist’s own imagination, and, as soon as they emerge, they immediately reserved an alcove of mental space for themselves.