The Taste of Mountains—Stories from the Bamboo Grove

| February 6, 2026

Text by Cao Yu

The vegetable and bamboo shoots in Manmai farmers’ market.

Photo by the author.

Manmai Market

I was fortunate to join the third leg of “Expeditionary Botanics,” a month-long project in the field organized by curator Dai Xiyun and artist Cheng Xinhao in April 2025. The expedition started at a subtropical river mouth and covered 4,000 km along Yunnan’s border, heading westward and then northward, concluding at the base of Jade Dragon Snow Mountain.

As our journey neared its end in Jinghong, our friend Zi Bai, one of the participating artists residing in Gasa, invited us to his home just outside the city. He proposed we gather ingredients from the nearby Manmai farmers’ market, located about 2 km north of his place, and prepare a meal together at his house. The market, known for its diverse local foods, operates from 4 p.m. until after sunset.

From Dehong to Xishuangbanna, we encountered many distinctive local foods—wild greens we couldn’t name, flowers we’d seen often but never eaten—all turned into ingredients. We had already sampled many of these in restaurants from Yingjiang to Mangshi to Jinghong to Menglun. Though it was late April and Yunnan’s famed mushrooms were not yet in season, the markets were overflowing with a variety of bamboo shoots and exotic plants. As someone who’s both a long-time cook and a food anthropologist, I was itching to try these unfamiliar ingredients.

The ingredient that caught my eye the most was the bamboo shoot—April is its prime season. There were at least seven or eight vendors selling them. Many stalls also sold sour sausages and sour pork, fermented with salt and rice powder. I had encountered these during past research on fermentation but hadn’t tried them much beyond sour fish. This time, I wanted to combine the two and make sour pork stir-fried with bamboo shoots.

The Song poet Su Dongpo (1037–1101) famously stated, “Without bamboo, one becomes vulgar; without meat, one grows thin.” This sentiment led to the popular saying, “Neither vulgar nor thin—every meal, bamboo and meat.” Traditionally, bamboo shoots were considered an “intestinal scraper,” believed to cleanse the body of fat. This nutritional understanding explains why fatty meats are often paired with bamboo shoots in dishes like oil-braised bamboo, pork belly with shoots, or smoked meat with shoots. Based on this logic, I reasoned that sour pork with bamboo shoots would also be a suitable combination.

Frying bamboo shoots with sour pork.

Photo: Zi Bai

The sour pork and sour fish made by the Dai people are part of an ancient tradition called zha (鲊). It was widely eaten during the Song dynasty (960–1279) in Jiangnan, the region south of the Yangtze River, and came in over ten varieties. But by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), doctors began warning that raw zha was harmful, so it became less common and started being cooked instead. Today, a dish still called zha rou survives—better known as steamed pork with rice flour. However, modern versions use unfermented rice flour, so the dish lacks the sourness of traditional zha. According to the ancient lexicon Erya, zha originally referred to food fermented with salt and rice, similar to pickled vegetables. Even modern Japanese sushi (written with the same character “鲊” in Chinese) evolved from this, as the rice is seasoned with vinegar—another offshoot of this tradition.

From Fresh to Bitter

The bamboo shoots I bought from Manmai were washed, peeled, sliced, blanched, soaked, and then stir-fried with sour pork. The yellow shoots and red pork made an adorable pairing. Once it hit the table, everyone eagerly reached for it. But within seconds, several people spat their shoots out. Someone exclaimed how bitter it was; another rushed to rinse their mouth at the sink. Those who only ate the pork stayed quiet. Those who got the shoots were visibly disappointed.

I tried a few slices myself—indeed, the bitterness was overpowering. Perhaps it had been too long since I’d eaten bitter shoots, and I couldn’t handle it anymore. When exposed to sunlight, the umami in bamboo shoots fades, and an amino acid called tyrosine breaks down into taxiphyllin, which has a bitter taste. If digested improperly, it can produce toxic cyanide compounds. In hindsight, the tips of these shoots did seem a bit green, though they hadn’t sprouted yet.

Despite their toxicity, bitter bamboo shoots are commonly eaten in the Hakka mountain regions where my family are originally from. A typical dish is bitter shoots stir-fried with pork belly. I remember having it often as a child visiting my hometown, but because of the bitterness, I never ate much. Years later, bitter bamboo remains as bitter as I recall. Zi Bai, seeing everyone’s surprise, said that in subtropical regions, bitter vegetables like bitter melon are common—and bamboo with a bit of bitterness isn’t unusual or alarming.

Even in ancient times, bitter shoots were recorded. The Song poet Huang Tingjian (1045–1105) once wrote an “Ode to Bitter Bamboo Shoots,” where he praised their subtle flavor and moral symbolism, even though he knew of their harmful properties. One quote stands out: “A touch of bitterness makes the taste.”

Suzuki Harunobu, Gathering Bamboo Shoots, c. 1765

Color woodblock print, 24.5 × 18.5 cm

Sour Shoots, Stinky Shoots

In recent years, due to the popularity of Luosifen (snail rice noodle) from Liuzhou, sour bamboo shoots have gained nationwide fame—mainly for their unapologetically long-lasting stench. Every Luosifen shop across China relies on this distinctive sour-stinky aroma to lure customers. Its smell travels far—often 50 meters or more—tempting lovers of pungency.

Though now known as a Guangxi specialty, sour bamboo shoots are actually common along the Nanling Mountains near the 25th parallel north. From Tianlin in Guangxi to Zhangzhou in Fujian, there exists a 1,300-kilometer-long “sour shoot belt,” where people of many ethnicities eat fermented bamboo. In northern Guangdong’s Hakka areas, it’s often called stinky shoot. The distinctive smell comes from the breakdown of cysteine and tryptophan into sulfur compounds and indoles during fermentation.

Sour shoots, despite their pungent aroma, actually enhance the natural umami of bamboo. The fermentation process tenderizes their fibers and locks in moisture, ensuring a crisp texture. Aside from their distinctive scent, sour bamboo shoots are a “cure-all” of food, perfectly balanced in all other aspects. For enthusiasts, the smell simply adds to their appeal.

Throughout history, access to fresh bamboo shoots has been a luxury, primarily enjoyed by emperors and their courtiers in the northern regions during the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). Even with modern air transport, fresh bamboo shoots sent to Beijing often lose much of their distinct flavor. Given their affordability and longer shelf life, sour bamboo shoots could offer a viable solution for northerners to experience the authentic taste of bamboo.

Bamboo Shoots and Mountain Regions

Though bamboo shoots are commonly associated with mountains, particularly in the southern highlands, this is a misconception. During the “Expeditionary Botanics” trip to Dehong and Xishuangbanna, the prevalence of mountain ranges seemed to confirm this stereotype. However, bamboo actually thrives in warm, humid valleys rather than mountainous regions.

The “mountain-grown bamboo” is a human construct. Historically, people cultivated flatlands for grain, forcing bamboo to higher elevations. The Song dynasty food expert Lin Hong (1127–1279) wrote in The Simple Foods of the Mountain Folk that early summer bamboo shoots were best when freshly roasted near bamboo groves. He said nothing of mountains—just forests. The commonality of the phrase “mountain forest” today reflects the scarcity of flatland forests, which have been transformed into cities, roads, and farmland.

The perception of bamboo shoots as a mountain delicacy is a constructed geographic landscape. This concept, drawing on Yi-Fu Tuan’s theory of “sense of place,” merges environmental shifts (bamboo’s migration to hills) with cultural beliefs (wild foods originate from mountains). The constructed geographical landscape of mountain-grown bamboo also reflects what Yi-Fu Tuan refers to as placeness: through continuous geographic transformation and cultural imagination, humans have intrinsically linked specific landscape features to particular geographical areas, ultimately forming a collective perception. This perception has overshadowed the botanical fact that bamboo naturally grows better in lowland river valleys.

Bamboo shoots have been a consistent part of the Chinese diet for over 2,000 years, even appearing in court offerings mentioned in the Book of Songs (an anthology of Chinese poetry dating from the 11th to 7th centuries BC). The Book of Songs: Airs of Wei includes the line: “Gazing upon the Qi River’s banks, the green bamboo sways lushly.” The Rites of Zhou (Zhouli) also records pickled bamboo shoots, all of which indicate that northern China produced bamboo shoots during the pre-Qin period. Agricultural development in northern China began earlier than the south, and bamboo in the northern plains was gradually displaced by grain crops. The mountainous regions of the north, being colder, were unsuitable for bamboo growth. Furthermore, a shift to drier and colder conditions after the warm Qin-Han period (221 BC–220 AD) led to the complete vanishing of large bamboo forests from the north by the Song (960–1279) or Yuan (1279–1368) dynasties.

Even today, a town in Zhouzhi, Shaanxi, is still named Sizhu (literally “bamboo office”), after the Tang, Song, and Ming government bureaus responsible for bamboo management. However, by the reign of Ming Emperor Yingzong, bamboo had almost vanished from the area.

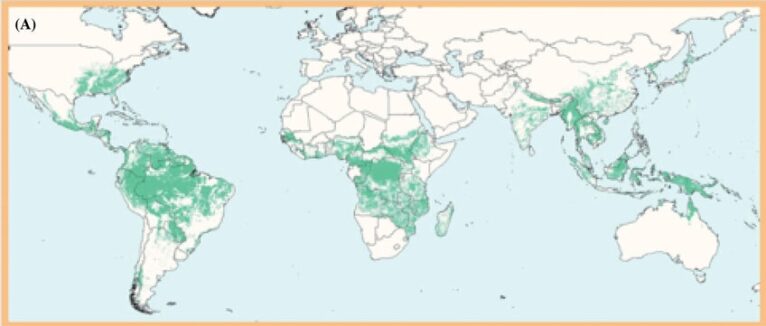

The atlas of bamboo. Source: Zhao, Hansheng et al. (2017). Announcing the Genome Atlas of Bamboo and Rattan (GABR) project: promoting research in evolution and in economically and ecologically beneficial plants. GigaScience. 6. 10.1093/gigascience/gix046.

Tasting the Freshness of Shoots

Though bamboo grows in many places around the world, only four regions—East Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Ethiopia—eat bamboo shoots. Of these, East Asia is the largest consumer, with China and Japan together eating 2.1 million tons per year (China 1.3 million, Japan 0.8 million)—95% of the world total.

This love of bamboo shoots stems from their umami. Containing 17 amino acids, they were one of the few sources of savory flavor before MSG. Like ham, scallops, and shiitake mushrooms, they enhance broths and elevate dishes. But bamboo’s umami is fleeting—its freshness is its virtue. East Asian taste aesthetics prioritize fleeting flavors over enduring ones, and vegetarian umami is more highly valued than meat. For instance, the ephemeral freshness of bamboo would be preferred over ham in a culinary context.

Bamboo shoots have been celebrated by writers across various dynasties. In the Tang dynasty, Wang Wei penned “Record of Winter Shoots,” and Li Qiao wrote “A Memorial Congratulating the Court on Auspicious Bamboo Shoots on Behalf of the Officials.” Lu Guimeng composed “Ode to Bamboo Shoots,” and literary figures such as Bai Juyi, Su Shi, Huang Tingjian, Fang Yue, Li He, and Li Shangyin all featured bamboo in their works. Li Yu even lauded bamboo as “the greatest of all vegetables.” The Simple Foods of the Mountain Folk by Lin Hong contains at least four recipes with bamboo. This rich literary history enhances the emotional and aesthetic appreciation of bamboo.

“All good things are fragile—like fleeting clouds or delicate glass,” as the old verse puts it. This fragility is evident in the umami of bamboo shoots; their amino acids break down rapidly, causing a loss of flavor within days. This inherent delicate nature is precisely why Lin Hong championed the principle of “freshness by the forest,” stressing the importance of harvesting and cooking shoots directly beside the grove.

Translated by Lai Fei

Cao Yu, born in 1984 in Guangzhou, is a food anthropologist, and a sharp-tongued chef with a wry sense of humor. His notable written works include A History of Chili-pepper in China (2019) and The History of Betelnut in China (2022). He currently teaches two courses at Jinan University in Guangzhou: Studies on Chinese Food and Foodways and History of Overseas Chinese Migration.