Transvestite Transliteration: The case of Uyghur versus Atatürk

| June 2, 2016 | Post In 2016年4月号

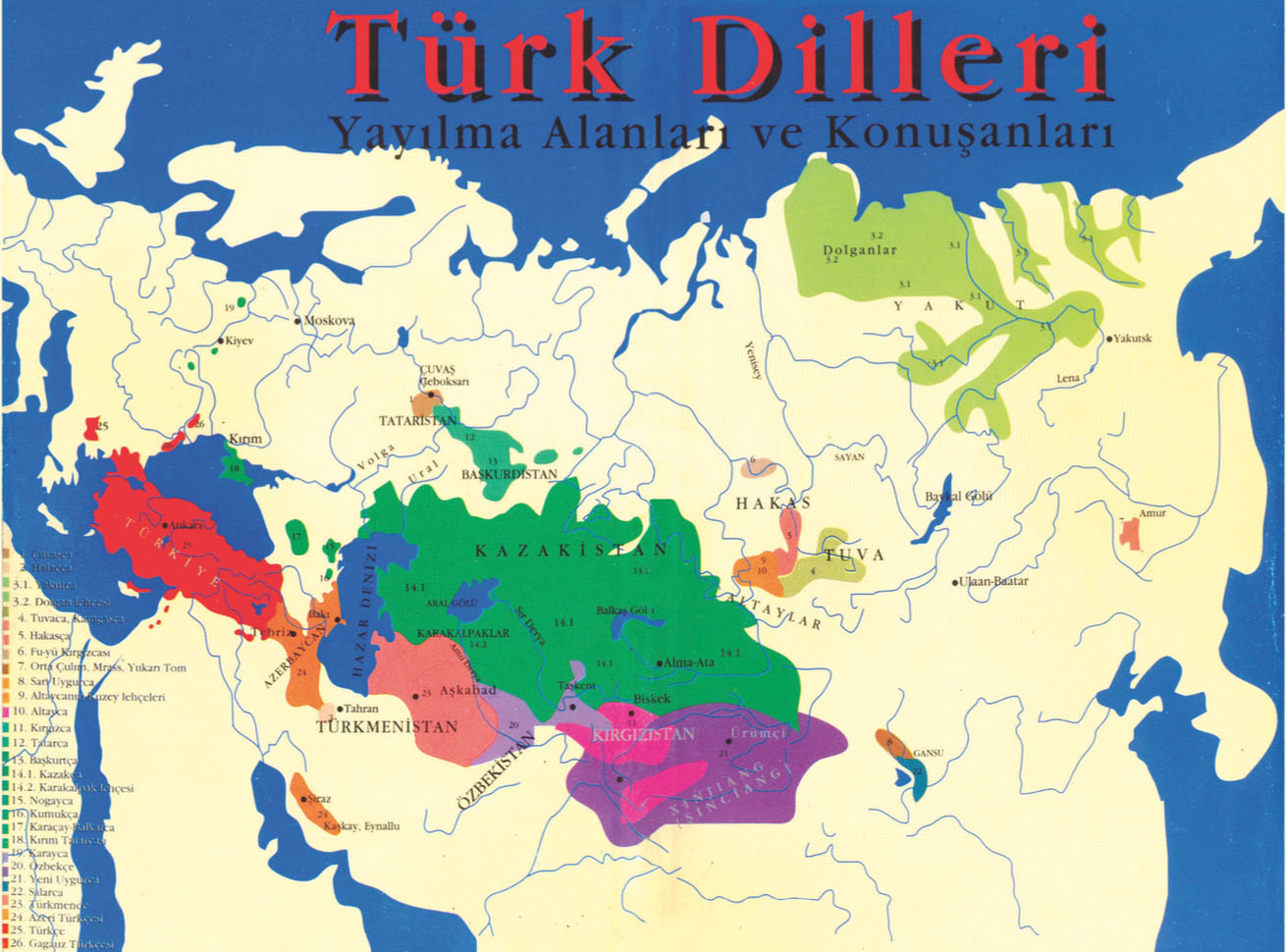

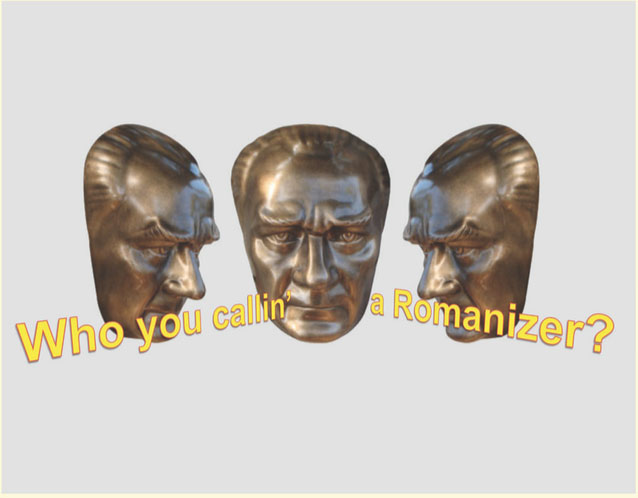

All across Xinjiang, the logograms of the Chinese language sit smugly below the teeth of the Uyghur Arabic script, each pictograph a comfortable caramel morsel in the mouth of the molar abjad. If there is a home for the Turkic languages, a group that extends from the Balkans to the Himalayas, it is not a geographic one, and certainly not the Anatolian behemoth that claims the mantle. The agglutinative group lays its head at an imagined if not internal abode, one at a physiological crossroads firmly ensconced in the soft palate at the back of the mouth where the nose and the throat meet. And no other grapheme but Kêf-î Nûni manages to better reconcile the two organs often upstaged by the tongue. While Ataturk hitched his republic and language to the west by Romanizing Ottoman Turkish, it’s not a coincidence that this particular phoneme, the nasal [ng] or velar was left behind.

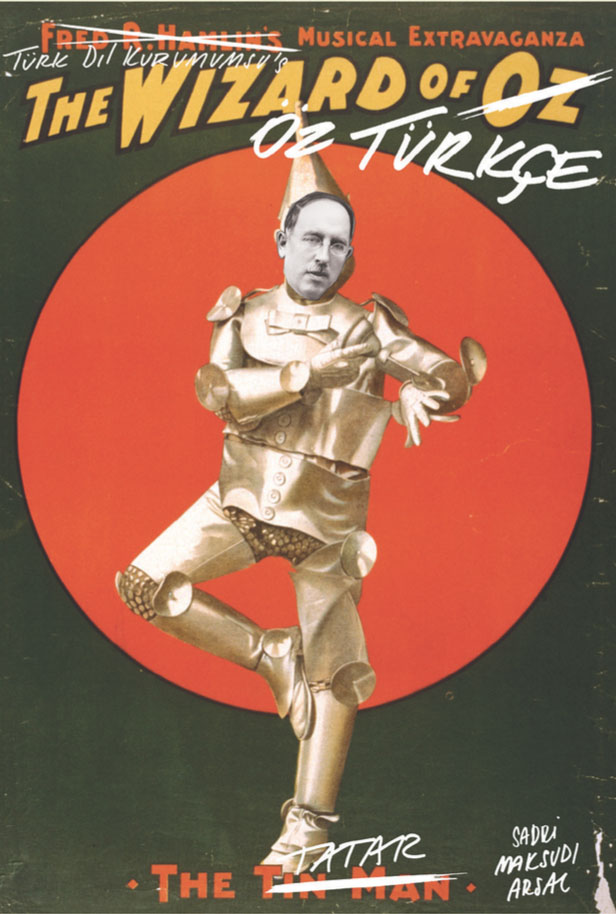

Paul Ricoeur defines translation as a form of linguistic hospitality, welcoming the Other into one’s own language and expropriating oneself into the language of the Other. Refuting the customary exegesis of Babel as a cautionary tale of human division, of linguistic diversity or the impossibility of translation, Ricoeur turns to another Biblical precedent, the pact of sacred hospitality shared among the three Abrahamic faiths, to redeem the “pleasure of dwelling in the other’s language … balanced by the pleasure of receiving the foreign word at home.” If translating a word from one language to another includes dusting off the family silver, then transliteration is akin to raiding mom’s jewelry cabinet, wearing the clothes of the Other. Our lecture-performance The Tranny Tease (2014) enacts the theological, semantic, and phonetic slippage that occurs when language dresses in drag.

It was via our translation of Molla Nasreddin that we first fell for the devastating tides of change that washed not only over Azeri but over other Turkic alphabets of Muslims under Soviet rule. Changing no less than three times in 70 years—from Arabic to Latin in 1929, Latin to Cyrillic in 1939 and Cyrillic back to Latin in 1991—the alphabet wars waged upon the region made peoples immigrants in their own countries. Cutting whole populations off from the Arabic alphabets of their Turkic languages and, namely, Arabic’s sacred role as a ‘script-world’ in Islam, Lenin believed that Latinizing the Muslim languages of the USSR amounted to the Revolution of the East. He did not live to see his initial error implemented nor compounded by his successor: a little more than a decade later, in 1939, Stalin opted for Cyrillic, from fear of pan-Turkism.

Among the letters that didn’t quite make it from the sinking ship of Ottoman Turkish to the newly Romanized shores was the 28th letterof the alphabet, a little twitch at the back of the nose, the ڭ or Kêf-î Nûni. Until 1928, the Turks had two different sounds: the conventional ن (n), the one you’d be happy to introduce to the parents, as in “ ن (n)”, ‘never’, or ‘nomenklatura’; then there’s the ,ڭ, a more peculiar, eccentric type of n, pronounced in the depths of the nose, as the <ng> in ‘sing’. The very pronunciation of <ng> has all the first-degree Oriental trappings of a snake-charmer, or more aptly, a gong. For good reason: ng does figure among the most common Chinese surnames, with an extensive Wikipedia entry dedicated to “Notable people with the surname Ng” to boot. In Turkey, words that used to have the ng have simply whitewashed it out of existence, like blacklisted party members from an official photo—an unwanted reminder of phonetic, linguistic, if not national disruption. Dengiz became deniz (sea), Tangri became Tanri (all-encompassing sky).

We demand elasticity not only from arms and legs, but also from other appendages. Other skies⋀orifices tell other stories, to misquote ourselves. A kef literally trying to hit the two distinct, diverging <n>’s, the limbs of our Nose Twister double as a nose and seat-rest. An urgent reminder of the very Asian origins of the Turkish language, this simple letter ڭ and endangered phoneme [ng] belie the westernization at the heart of Atatürk’s founding of the Turkish Republic. From China to Vietnam, across southeast Asia—not to mention the diaspora—millions named [ng] would like to ask Kemal: why the snub, ol’ Blue Eyes?

With not a single ü, ö or ğ anywhere in sight, Xinjiang, at the far end of the continent, doesn’t come across as the most intuitive place to understand contemporary Turkey. The Ottoman Empire pushed west and southwards, leaving its eastern flanks, where most Turkic peoples historically reside, under rival Russian rule. While Tatars, Circassians, and other inhabitants of the Caucasus and central Asia have moved westwards, to Turkey, the counter orientation, eastwards, has not been equally embraced. Indirection is something we cultivate, ferment, even pickle. It allows us to embark on the ideological and historiographical equivalent of a tongue-twister, entangling ourselves, literally, into knots. Given the hardcore heterogeneity involved in being Ottoman, the transition to national identity that resulted from the founding of Republic of Turkey, at the expense of Armenian, Kurdish, and also Bosnian, Albanian, and Tatar, to name a few, was regrettably often reductive. Thankfully, Uyghur attempts have gone the other way around, taking a rather expansive view to correct the situation. As David J. Brophy sums up:

“Most studies which treat the formation of a national community begin by analyzing the intellectual explorations of that national identity, which lay the foundations for its subsequent politicization, and the emergence of nationalist activism, usually leading towards the goal of a sovereign nation-state. The Uyghur case does not follow the same progression of stages. Here, the political use of Uyghur identity precedes any sort of consensus on the nature of that identity. Or, to put it slightly differently, the small group of people who identified as Uyghurs found themselves in a position to project the name over a much wider section of the population, in a way which calls to mind earlier periods of Central Asian history, in which terms such as “Turk” or “Manchu” signified political projects before they signified ethnicities.”

Courtesy of Istanbul Modern.

The cadences of script changes in Uyghur recall those of Turkic peoples in the former Soviet sphere, with the added lilts of twentieth-century Sino-Soviet relations. Uyghurs lived on both sides of the border delineating China and the USSR (present-day Kazakhstan). Those on the Soviet side underwent Romanization from 1930 to 1946 and adopted a Cyrillic script in 1946. On the Chinese side, however, Romanization remained ineffectual, and Arabic script was largely in use until the 1950s, when the alphabet became a victim of the brief midcentury bromance between the USSR and a newly communist China. Seven years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, in 1956, with some nudging from the Soviets and initiative from Uyghurs themselves, a Cyrillic script was adopted, albeit experimentally. Our beloved Kêf-î Nûni or ڭ was reborn as Ң. But the flame burned quickly: in 1958, after only two short years, Sino-Soviet relations cooled, and a Pinyin-based Latin script was introduced to the Uyghur language.

In the waning days of the Soviet Union, the imminent independence of the central Asian republics was seen as a historic opportunity for Uyghurs across the border in China to follow suit. After all, their fellow Turkic neighbors and co-religionists the Kazakhs, Turkmen, Uzbeks, and Kyrgyz would inherit nation states for the first time in recorded history. Why not the same for Uyghurs? In 1982, with very little documentation and discussion, the Arabic script was reintroduced, in what was considered a victory by the Uyghurs themselves. In retrospect, though, it is difficult not to see this return to Arabic as an uncannily prescient strategic move on behalf of the Chinese authorities. When the calls came to return to the Latin script in newly formed Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, the Uyghurs could no longer look westwards for the sympathies of a common script.

In Domination and the Arts of Resistance, James Scott turns to the private domain of the oral in speech, songs, and gestures as a form of opposition that escapes even the most cruelly oppressive regimes. Too often, he argues, political scientists and experts track only the explicitly overt and organized manifestations, those most often successfully suppressed by the authorities. The term he coins to describe this form of resistance, infrapolitics, is a compelling one. Perhaps we could bleed this term to its very literal edges—that which takes place under and below the tongue—as evidence of the erogenous, fleshy role of language amongst the Uyghurs as well as the Turks, Poles, or any other peoples who have experienced the tumult of swaying scripts. To unravel the twisted nexus of politics, affect, and society at the heart of alphabet politics, we need a full arsenal of nose-, throat-, teeth-, ear-, lip- and tongue twisters.